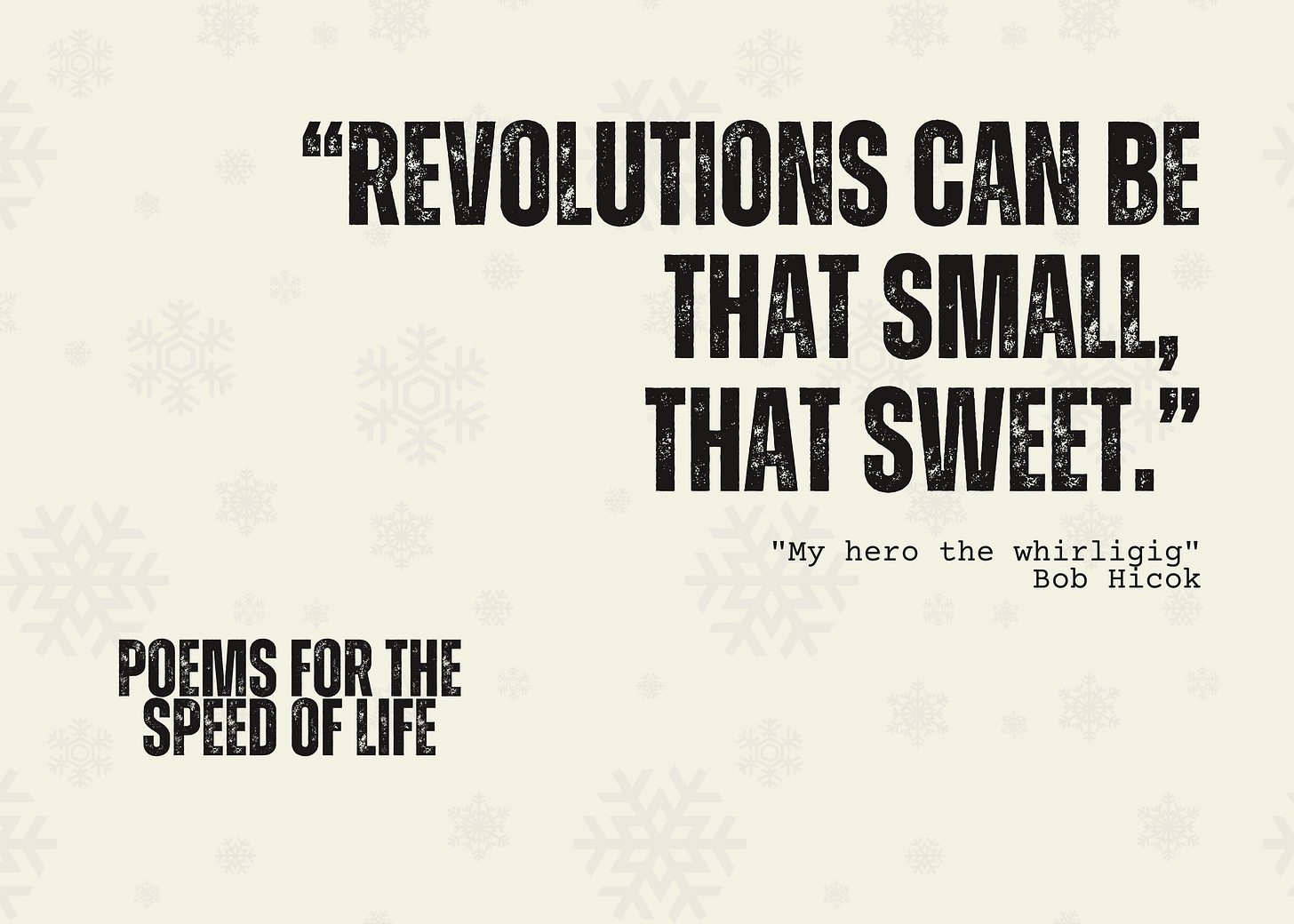

S4, E7: "My hero the whirligig" by Bob Hicok

The seventh episode of the new series of Poems for the Speed of Life, on the theme of Christmas. "My hero the whirligig" by Bob Hicok.

Welcome to another episode of Poems for the Speed of Life with Shane Breslin, entrepreneur, writer and poetry advocate.

This is the seventh episode of a new series of the podcast, poems on the theme of Christmas. Today’s piece is "My hero the whirligig" by Bob Hicok.

If you’d like to read along while you listen, you can find "My hero the whirligig" by Bob Hicok.

Commentary on "My hero the whirligig" by Bob Hicok

Bob Hicok is an American poet and I found this poem through a Substack dedicated to his work. It’s run by Karan Kapoor, the Editor in Chief of the Only Poems online literature magazine, who writes that “Bob Hicok, in many ways, is the reason I write and continue to fall in love with poetry every single day.”

Among many other literary prizes Bob Hicok has received a Guggenheim award, nine Pushcart Prizes, and was twice a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. His poems have appeared in nine volumes of the Best American Poetry and Water Look Away, his 11th collection, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2023.

On the Poetry Foundation website, there’s a part which says when Hicok was asked by an interviewer about the way revelation takes place in his poems, he said, “Because I don’t know where a poem is headed when I start, it seems that revelation has to play a central part in the poems … what I’m most consistently doing is trying to understand why something is on my mind… Maybe writing is nothing more than an inquiry into presences.”

This poem, My hero the whirligig, is a perfect example of that. It seems to transform itself right before our eyes. It begins with childhood Christmas disappointments — the grand designs and grand desires we want for our lives. He puts forward Christmas wish lists as a microcosm for this desire for something more, something bigger for our lives. The narrator of the poem has the impossibly specific and impossibly grandiose wish to be “raised in a home for future stars of sitcoms”.

(The sitcoms themselves are absurd and hilarious: Jesus the gynecologist! A NASCAR racer who could only drive the wrong way!)

As the poem progresses, through that other absurd device of the 50 in 1 electronics kit that goes on to have a grand existence of its own, sending home photos of its life milestones, we finally get to discover something far more magical not in the things we desire and the things that are missing, but in the things that are overlooked, the things that are actually here. The poem shifts in one line partway through - “God I hate this: another poem about what's missing”.

It's like the narrator or the poet catches himself in the act of looking with longing past the present moment.

What follows then is an extraordinary revelation. He takes a fresh-eyed and urgent inventory of what is present:

“I see my hands, an open book about art, what appears to be the Earth outside my window.” There's something vital here — in the way the poem shifts from lavish and crazy desires to the mundane and everything things around us — about how we often miss the life we're actually living because we're too busy imagining a different one.

Those sitcom dreams at the start — "Jesus the gynecologist, the NASCAR racer, the girl with a skipping rope solving crimes — are funny, yes, but they're also about wanting to be something other than what we are. The 50-in-1 electronics kit from Radio Shack was not what was asked for, but look what happens when he starts to appreciate it. The poem transforms disappointment into discovery, the ordinary into the extraordinary.

This carries on into what happens when we leave aside the things we wish we could be and open ourselves up to the things that already are. The lines

“one day you'll wake up. Not to an alarm clock, not so you can swim the English channel, not in a fog or haze or city overlooking the Danube, but to a tone, a clear, precise tone like the sound you've always imagined stars would make if you could put your ear firmly against the night.”

This reminds me of that book by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince, where the prince gives the narrator the gift of hearing all the stars laugh.

And what is possible when we open ourselves up in this way? When we see and perceive things closely, and truly? It is that we then begin to see the wonder in the strange, crazy, beautiful hybrid of identities that go into making us us.

Those words — you are “half bird half ukulele” or “quarter volcano and three quarters Leonard Bernstein”.

In our digital age — I’m recording this in December 2024, as the world gets to grips with all the power and possibilities and pitfalls of AI technology, of the general breakdown in trust in media and institutions and leaders everywhere — we are all exploring who we are, together and apart, in real time. We craft our own identities through various prisms and lenses. We put versions of ourselves into the world that we think we want the world to see. Or we withdraw from it, worried by the very real concern that everything we say or do in a digital world will be passed through some filter — a digital filter or a psychological one — before it settles into the mind of someone on the other side, and we realize we have no control, none at all, over how that filter actually works.

And so if we’re driven to step away from the digital and embrace the world around us, a physical world where we might be able to trust our senses, who can really blame us?

This, I think, is part of what the poem is inviting us to do, but even as it does, it knows that this unfurling of identity is complex, and not without some pain or struggle.

The poem ends with this image of the helicopter, spinning and rising.

“Why should helicopters have all the fun?” Hicok writes. “We too can spin and spin and rise.”

Spinning is often associated with chaos or lack of direction, but in the case of the helicopter, the spinning becomes the thing that brings about the elevation. Maybe in the apparent chaos of our latent desires and the chaos of our mixed up identities, might that chaos contains the seeds of our ascent.

The life we think we want might not be the life we want at all.

And the life we want might only be slipping through our fingers because we haven't yet learned to see it.

Our moment of realization and awakening can happen at any time. Like baking a cake.

“Revolutions can be that small, that sweet,” as he writes.

As always, all of these thoughts are just my own, and I invite you to let it speak to you however it does. Your responses are always yours, and they are always valid.

Thank you for listening, and I'll see you again soon, for another episode of Poems for the Speed of Life. Take care.

Thank you again for being here.

I’ll be back soon with another poem in this series, the Christmas series, where I am trying to introduce you the listener, wherever you are in the world, to some of the writers who have masterly managed to capture things that are almost impossible to capture, the feelings of goodness and peace and love that this time of year brings to our families and our friendships and our hearts and our minds.

See you next time on Poems for the Speed of Life.

The Christmas Series

This is a poem from the Christmas poems series of Poems for the Speed of Life.

I know there are listeners and followers of this podcast all over the world. I know that there are many people here with many different religions, and many different faiths — or none — and I know that Christianity is just one.

If a series about Christmas leaves you in any way cold or distant, let me say that the goal of this series of the podcast is not to evangelize about Christianity, nor to show the benefits of one way of being or thinking or believing at the expense of all the others.

What it is, though, is my attempt to create something that captures something of the goodness of this time of year.

Because when I think of Christmas, and when I put aside all the dogmas of us-versus-them religion, and when I put aside the mass consumerism of the so-called “shopping season”, and when I really think of this time of year, of these few weeks each December, what I think, and what I feel, is captured in one or two words.

Goodness. Love.

When you’re about on the streets at this time of year — and yes, I’m probably talking about Europe, or the Americas, or the other places that might be part of so-called “Western Civilization” or the “Western Hemisphere” — there is something always good in the air. It is something that contains magic.

It is communal. It is generous. It is kind.

It is goodness.

It is love.

And maybe — for who am I to have any certainty about what is and what isn’t? — maybe it is God’s love, maybe it is the love of Christ, that comes to us and through us at this time of year.

Whatever it is, it is a love and a goodness that never — not in my experience anyway — comes fully through the giving or receiving of gifts, but arrives in the space between. In a quiet moment. In the look in a loved one’s eye or some fleeting moment on the street or at work, when something passes unsaid, something that remains unsaid because we might not have the words to say it, but is still somehow completely understood.

And so, this series of the podcast will include poems, and some other pieces of writing, that touch on this. Poems and passages of writing that actually do find the words that capture some of that wonder and magic. Some of that invisible spirit.

Some of that goodness. And some of that love.

Long-time listeners will know that I sometimes broaden my definition of what a poem is to include in Poems for the Speed of Life.

Sometimes I offer song lyrics, as in “The Best Day of My Life” by Tom Odell in Episode 30, “The West Coast of Clare” by Andy Irvine in Episode 45, and “The Living Years” by Mike Rutherford, in Episode 2 of the recent Fatherhood poems series.

I will do that again in this series, with a song written by an Irishman who said he has written dozens of — in his words — “dreadful maudlin songs”, but that this one came to him from somewhere else, some other place, some unseen but always present source of creativity.

Sometimes I offer sections of prose that, to me, carry all the power of poetry, like “Desiderata” by Max Ehrmann in Episode 165 and a passage from Vaclav Havel’s “Hope” in Episode 187.

In this series I will include, again, the long prose poem by Dylan Thomas titled “A Child’s Christmas in Wales” and the series will also feature a segment from “A Christmas Carol” by Charles Dickens, which, no matter how good and how memorable all the various movie adaptations might be, stands above them all as a peerless work of writing. I aim to read both Dickens and Thomas every December in any case, and here I will read them for you.

I will read a newspaper editorial published in the 1890s, and I will also, of course, read poems — by an English poet laureate, by a late great Irish poet, by several Americans, dead and alive, and by others, from elsewhere around the world.

This series is for everyone.

It’s for everyone who might want or need to feel some of this goodness and some of this love, especially in our world which sometimes seems like it’s in short supply of both.

It will be for everyone who wants to give generously, and not just in material or monetary ways, but in the generosity of spirit and consciousness and goodwill that will always be useful, and cherished, by the people you come into contact with.

I look forward to bringing you the new series of Poems for the Speed of Life, on Christmas, starting with Episode 1, on Saturday, November 23rd and continuing through December 2024.

Thank you for listening. If you’re not already subscribing or following, please do so, for free, in your podcast app or in Spotify. Keep an eye on your podcasts feeds, and you’ll be hearing from me again very soon.

See you soon.

For a detailed outline of the mission and purpose behind this podcast, please check out these two episodes:

If you’re on social media, you can follow on Instagram here and Facebook here.

You can subscribe to or follow the show for free wherever you listen to podcasts.

To leave the show a review:

On Spotify. Open the Spotify app (iOS or Android), find the show and tap to rate five-stars.

On Apple. Open your Apple Podcasts app, find the show and tap to rate five-stars.

On Podchaser. Open the Podchaser website, find the show and tap to rate five-stars.